When speaking to lovers of dark roast (by this, I mean my dad), I often compare this style of coffee to heavy red wine: sometimes it is produced from grapes picked so ripe that the alcohol is super high and the tannins quite intense...and then on top of that, if the wine gets aged in new oak barrels, this completely overshadows whatever subtlety was left. In the end it becomes impossible to taste the grapes that once grew in a field. The same goes for roasting.

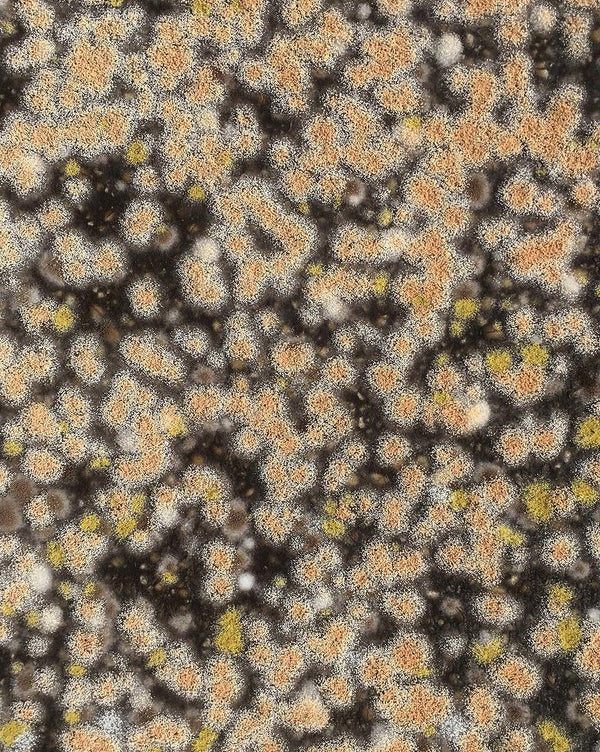

Of course, a light roast needs good fruit: no way to char your way out of an unripe or half-rotten cherry. And to get good fruit takes more than just good farming; it takes harvesting the fruit at the right time. Picking ripe coffee cherries is essential for specialty coffee, and it requires a lot of patience and care. Unlike a bunch of grapes harvested all at once, with the coffee tree you need to return again and again over the course of weeks to make sure you get just the right ripeness. Most large plantations and coffee growers will pay no mind to this—especially if the coffee beans are roasted very dark, which makes it easy to mask any flaws. Training workers in the fields to know which fruit is ripe for picking takes time and effort. But it pays off.

With this month’s coffee delivery, we begin to send the fruits of our very first origin trip: a whirlwind across Colombia's main coffee-growing regions to spend time at some of the small farms whose coffees we have long loved from afar.

The slopes of Pitalito, Huila

We chose two different varieties from the same farmer: Carlos Guamanga in Pitalito, Huila. At his farm Finca El Recuerdo the effort and dedication of him and his wife Patricia is clear to see: the farm is carefully put together and thoughtfully managed, with beautifully maintained drying beds and a stunning view of the valley. The slim path to the coffee trees leads through a protected forest with butterflies and bright flowers fighting for your attention. This forest is not only a thing of beauty: it provides the farm with a natural source of clean water. Back in the courtyard, we speak of all the plans Patricia and Carlos have made for the future– a list of things that could be improved and built upon. But we also speak of the past, where they come from, and how hard they worked to get to where they are now. It is the reason they named their farm ‘The Memory’: a testament to what it takes to build a healthy coffee business in Huila, Colombia: from the moment they met almost two decades ago, they started building their dream. Not easy, in a country where there is stiff competition for farm labor. Let’s be real: when we talk about Colombia, a different plant and its stimulating effects are never far from the conversation.

On our travels, we spoke to many locals about the influence of cocaine cultivation on culture, on village life, and on the choices young people make. Why pick coffee beans when you can get paid so much more picking coca leaves? A real question that troubles coffee farmers as they seek laborers to help them in the fields during harvest time.

Pickers’ backpacks, hung across a border fence

There is so much that is overlooked when we think about paid labor on coffee plantations. Yes, you may be paying a good price for the beans, but what does the picker earn? Is a spouse working all day without pay? Does anybody have insurance of any kind? What is a living income, and who decides that? Important questions we found ourselves asking. Luckily, we came across so many great initiatives.

Freshly picked coffee cherry

Like The Pickers Project, which contracts pickers and provides salary, healthcare, and training. Both sides benefit: there is an incentive to come and work in coffee and the harvest is done with care and, not unimportantly, joy.

Another example is The Sustainable Coffee Buyers Guide, which maps the different coffee-growing regions and outlines what constitutes not only a living wage, but a prosperous wage. Namely, the ability to feed and also to save, to reinvest, to build.

All of the Colombian coffees that we will be serving with Noma Kaffe are picked in collaboration with the Pickers Project (or Manos al Grano). If you want to know more about these projects, and the faces behind the harvesting of your cherries, have a look right this way.